Ryan “Rhino” Bourland and his Quest

by Diane Ketelle

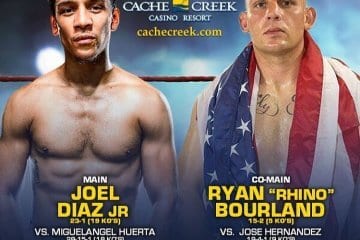

(Photograph by Lucas Ketelle)

A rhinoceros, often abbreviated to rhino, is characterized by its large head, short neck and large horn. The rhino is massive and intimidating, but also agile, and at times, even vulnerable. When I first met Ryan “Rhino” Bourland, a young light heavyweight professional boxer, I was struck by how his moniker matched his physical stature. In addition to his size, Ryan seemed to possess other “rhino-like” qualities: he hunched his large shoulders slightly as we talked, and although he was large, moved with a certain gentleness. Ryan’s attitude is all the more surprising considering his rank and burgeoning career as a heavy hitter. Ryan’s world ranking is 131 out of 1,144 light heavyweight boxers and his U.S. ranking is 31 out of 191. His goal is to move his ranking up with each fight.

At first glance, Rhino’s story may appear to be just another boxing cliché: a predictable exposition of the master narrative of boxing. That version goes something like this: Rhino was a tough kid who got in trouble, got into fights, and had a dim future, but a growing interest in the sport of boxing helped him develop the discipline he needed to turn his life around. Rhino’s story is actually more nuanced than that narrative and Ryan himself is more than a composite of boxing protagonists.

Rhino was born in Vallejo, California and grew up in a white, working class neighborhood. He lived with his brother, sister, and his parents until they divorced when he was fifteen. His neighborhood was made up of Latinos, Blacks, and white working class families. The elementary and middle schools he attended were racially charged: “The white kids and the Black kids fought all the time over nothing,” he said. Rhino was a loveable bully, often fighting to defend other students at school who were being picked on. “I don’t like to see people who are vulnerable being made fun of – it really gets to me.” He knew he was a good fighter and when he got into fights he usually won, but he also found that fighting did not quell his anger. The anger, or its possible source, is more difficult for Rhino to discuss. “It is the past,” he says simply. He does not speak about pain, but I know it is there, and I also know that he has had to work through a lot to get where he is today. He describes most of the fights he got into as semi-playful, rough and tumble, kid’s stuff. Sometimes they were more serious, set off by some actual or perceived moral slight. Sometimes Rhino was defending the underdog—sometimes he was the underdog. He does not try to rationalize his rowdy youth. He is both honest and matter-of-fact about his past. He says: “Look, I also just got into a lot of fights.” He also acknowledges that for a long time he thought that strength and winning the fight was all that mattered—a sort of “might is right” mentality.

In middle school, Rhino’s parents became frustrated with his aggressive behavior and unchecked anger. They decided to put him in a special youth boxing program. Rhino loved the boxing program, but it did not keep him from getting into trouble. By the end of middle school, he had aged out of the program. His parents got divorced and he began to get into a lot more fights and found himself in minor scuffles with the law. “The divorce got me all torn up,” he said. He was in juvenile hall fifteen times during that period. From age seventeen to eighteen he was locked up in the California Youth Authority. “I did a lot of stupid stuff,” he said, but did not delve into the details of his offenses. Shortly after being released from the California Youth Authority, he was arrested two times for driving under the influence and the court sent him to a rehabilitation program for alcoholism. In the rehabilitation program, he met a counselor who encouraged him to begin training at a nearby boxing gym, and would allow him to leave early in the evenings to do so. Meeting this man was a kind of turning point. He was at a critical point in his life; he was aware that he needed to make serious changes, but found it difficult to implement change and get himself on the right track.

It was at this point in Rhino’s story that boxing took on enlarged significance. He needed a passion and a focus. Going to the gym every day helped him focus on the goal of being a boxer. “I had gained a lot of weight – I was about 250 pounds…at the gym I started losing weight, getting strong, and taking control of my life.” He also mentioned that “the gym got me away from people I knew I should not hang out with.” As he trained, he started to see the results of his work in the way his body began to look and he liked the changes. “I started feeling a lot better about myself,” he says.

After finishing the rehabilitation program, Rhino took a job working for his uncle in construction, where he still works today. Rhino likes working construction because it is physical and his uncle is willing to be flexible when it comes to his training schedule.

Recently, Rhino was asked if he would be willing to coach youth full-time. Currently, he coaches three days a week and works in construction the remaining two days. The transition to full-time coach would mean he would have to take a sizeable pay cut. His girlfriend and close friends have encouraged him take the leap because they know how much he likes working with young people. He says, “I love working with kids. I love boxing. Some of the kids are knuckleheads and they relate to me, and I relate to them. I make them work hard and they listen to me when I talk to them about their lives.” Rhino wonders what his life would have been like if he had met someone like himself, a mentor, when he was in middle school.

Ryan has had difficulties in his life, but he realizes that adversity can also create opportunities for a person to grow, develop, and adapt. . This aspect of Ryan, the reflective aspect, shatters stereotypes found in boxing’s master narratives. Getting to know Ryan pushed me past a simple boxing story as I explored the life of a complex man who is ambitious and determined, as well as compassionate and kind.

Diane Ketelle is a boxing fan and the Dean of the School of Education and the Wert Professor of Education at Mills College in Oakland California.